Before there was the African American Cultural Alliance of Lancaster, there were the Elks parades. There were drill teams marching through neighborhoods. There were institutions like Crispus Attucks and the Urban League anchoring culture in the city.

Vincent Derek Smith remembers those days.

“We’re not recreating anything,” he says. “We’re bringing it back.”

For Vincent, President and Founder of the African American Cultural Alliance of Lancaster and a 2002 graduate of McCaskey High School, the work hasn’t been about creating something new. It’s been about revival.

Formed by two cities and a village

Vincent was born in Lancaster and raised between Lancaster and Philadelphia. His early years at Mary McLeod Bethune Elementary School in Philadelphia shaped his understanding of identity and history.

“They taught it right,” he says. “Black history was a part of the curriculum, not just during Black History Month.”

History wasn’t confined to a single month. It was woven into daily instruction. Students learned about leadership, resilience, and achievement as part of their academic foundation.

When he returned to Lancaster and later graduated from McCaskey in 2002, he was still trying to find direction.

“I wasn’t the good kid back then,” he admits. “I was trying to engage and trying to find who I was.”

What shaped him wasn’t perfection. It was accountability. Family members were active in grassroots work across the city. Teachers invested in students beyond the classroom. Elders were visible.

“There was more of a sense of village,” he says. “If I did something, I knew it was going to get back to my grandma.”

He grew up surrounded by African American institutions that were thriving. Drill teams marched proudly. Parades filled city streets. Community centers served as cultural anchors. In his view, the African American Cultural Alliance exists because some of those traditions faded and someone needed to ensure they didn’t disappear.

A vision sparked in Philadelphia

After graduating from McCaskey, Vincent spent time in Philadelphia searching for clarity about his future. It was there, standing in the middle of the ODUNDE Festival, the largest African American street festival in the nation, that his perspective shifted.

“It wasn’t like Coachella with some big stage,” he remembers. “People were coming for the culture. That was the draw. The culture.”

What he saw wasn’t spectacle. It was ownership. Entire blocks lined with Black owned businesses. Families investing in one another. Leadership visible in every direction.

“I realized there are Black people who own businesses. Black people who are leading community organizations. Black people who are making changes,” he says. “I can do this too.”

That realization followed him home. Why didn’t Lancaster have something like this? Why should families have to leave their hometown to celebrate their culture on that scale?

From drill team to cultural platform

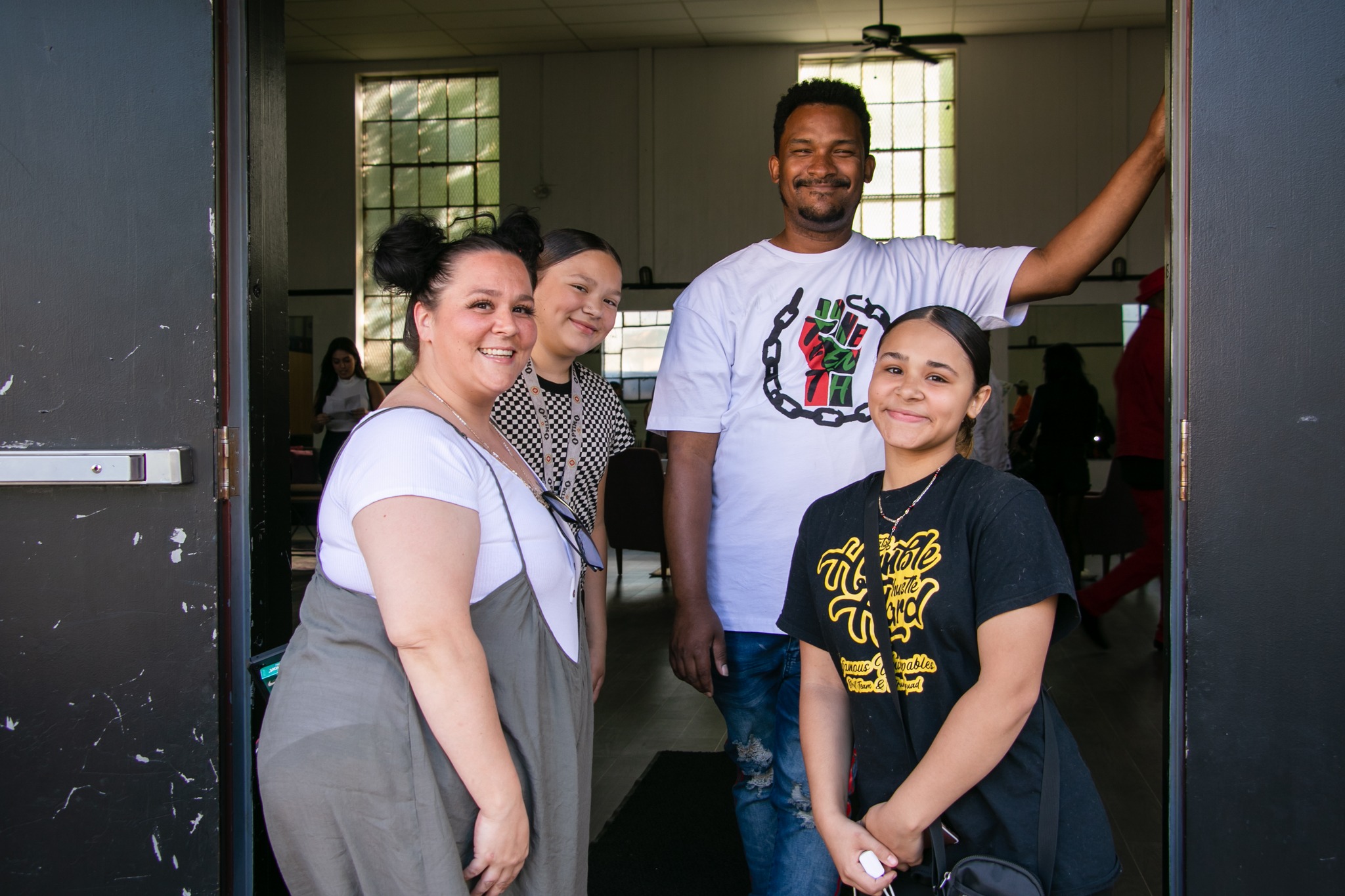

When Vincent returned to Lancaster, he approached Cheryl Holland Jones with an idea to restart a drill team.

“She gave me the opportunity to live my dream,” he says. “She didn’t know what risk she was taking.”

He didn’t come with funding or infrastructure. He came with conviction.

The drill team grew. Former members returned. Families reconnected. What began as youth programming expanded into the African American Cultural Fair and Parade.

“There were Latino festivals, the Greek festival, the Irish festival,” he recalls. “But there was nothing celebrating and recognizing African American culture here.”

The Alliance set out to change that. Its focus centers on cultural arts and preservation while creating economic visibility for Black owned businesses.

“Our focus is cultural arts and cultural preservation,” Vincent says. “We want people to understand what Black excellence looks like, feels like, and can be a part of.”

Generations returning

One of the clearest affirmations of the work came when Vincent restarted the drill team more than a decade ago. The drill team now lives at Bethel AME, the oldest black church in Lancaster.

“Former members came back,” he says. “And they brought their kids.”

Young people who once marched under his leadership returned as parents. They wanted their children to feel the same sense of discipline, pride, and belonging.

He also recalls a student who participated during the program’s time at Crispus Attucks and later connected to Lancaster Country Day School, ultimately graduating from there. Vincent believes that exposure and relationships built through drill team opened doors that might not have otherwise existed.

A former participant once told him, “Drill team made me proud of who I am.”

That affirmation stays with him.

“I find it important that you know who you are,” he says. “You shouldn’t have to travel outside of your community to celebrate it. That’s every culture. You should have the opportunity to celebrate your culture in your community with pride.”

The cost of carrying vision

Behind every parade and performance is sustained effort.

“Yes, there were moments when I almost quit,” Vincent says. “The battle isn’t easy.”

Most members of the Alliance board work full time jobs elsewhere. Meetings happen after hours. Sponsor engagement requires coordination and flexibility. The responsibility of carrying a long term vision without full time infrastructure can weigh heavily.

“It becomes emotionally stressful because you see the bigger picture,” he explains. “You see the vision. But without the correct support and guidance, it can challenge you.”

This year, the parade won’t take place in its current form. The decision reflects financial realities and a shifting sponsorship landscape around diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, along with construction along the traditional route.

“It doesn’t make financial sense for us this year,” he says honestly.

The pause isn’t abandonment. It’s stewardship.

“How do we ensure that it’s led by the people it’s meant to represent?” he asks. “Who do we pass the torch to? How do we keep it alive?”

Legacy and responsibility

When Vincent reflects on what keeps him up at night, his thoughts turn to history.

“I see those ancestors that went before me,” he says. “Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X. They understood there was a need in the community, and they stood up.”

He believes communities are once again in a moment that requires intentional preservation of culture.

“We can’t rely on government. We can’t rely on other people to do it for us,” he says. “We have to do it for ourselves. But we also need people in certain positions who can help us with connections and resources to ensure that Black culture doesn’t die.”

For him, Black History Month isn’t ceremonial.

“Black history lies in the community,” he says. “We have the responsibility to keep it alive.”

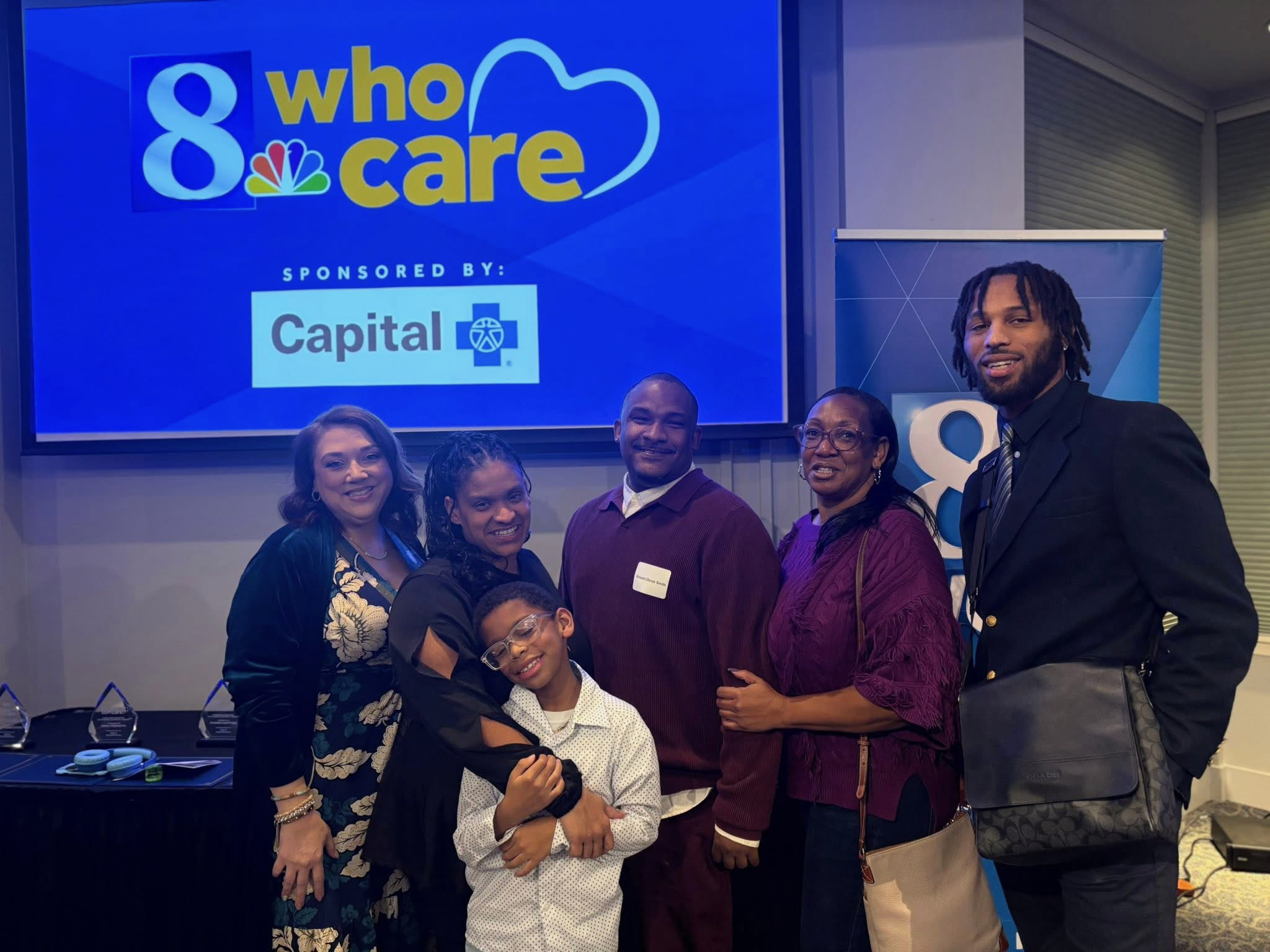

A McCaskey graduate still building

Vincent speaks with pride about being a McCaskey graduate.

“You can’t hide my McCaskey pride,” he says. He was named McCaskey Distinguished Alum in 2022

He remembers a school connected to its neighborhoods, where teachers were visible beyond the classroom and traditions created unity. That experience shaped his belief that institutions can anchor culture when they choose to invest in it.

He acknowledges ongoing challenges, including limited resources and assumptions about potential.

“We build with what we got,” he says. “That’s the difference.”

“I am the work”

When asked who he would be without this work, Vincent pauses.

“I don’t know,” he says. “The work became me. The culture became me. I love to see the community come together and celebrate who they are. I am the work.”

His leadership isn’t seasonal. It isn’t confined to February. It’s daily, relational, and often unseen.

During Black History Month, the School District of Lancaster honors leaders who carry forward the legacy of those who came before them. Vincent Derek Smith represents that continuation. His journey from McCaskey student to cultural steward reflects the power of mentorship, revival, and sustained commitment.

Lancaster’s cultural landscape looks different because he stayed.

The parade may pause. The work continues.